Freezing drizzle used to be an easy decision when I flew only piston equipment. Even the most robust piston airframes can’t keep up with this kind of “winter fun.” Ironically, the problem was not the cold, but that it was “warm” for February. The usual “minus whatever” would have been fine for flying; everything is glaciated. Freezing temperatures right at the surface and lots of moisture were going to be the challenge for this flight.

Freezing drizzle used to be an easy decision when I flew only piston equipment. Even the most robust piston airframes can’t keep up with this kind of “winter fun.” Ironically, the problem was not the cold, but that it was “warm” for February. The usual “minus whatever” would have been fine for flying; everything is glaciated. Freezing temperatures right at the surface and lots of moisture were going to be the challenge for this flight.

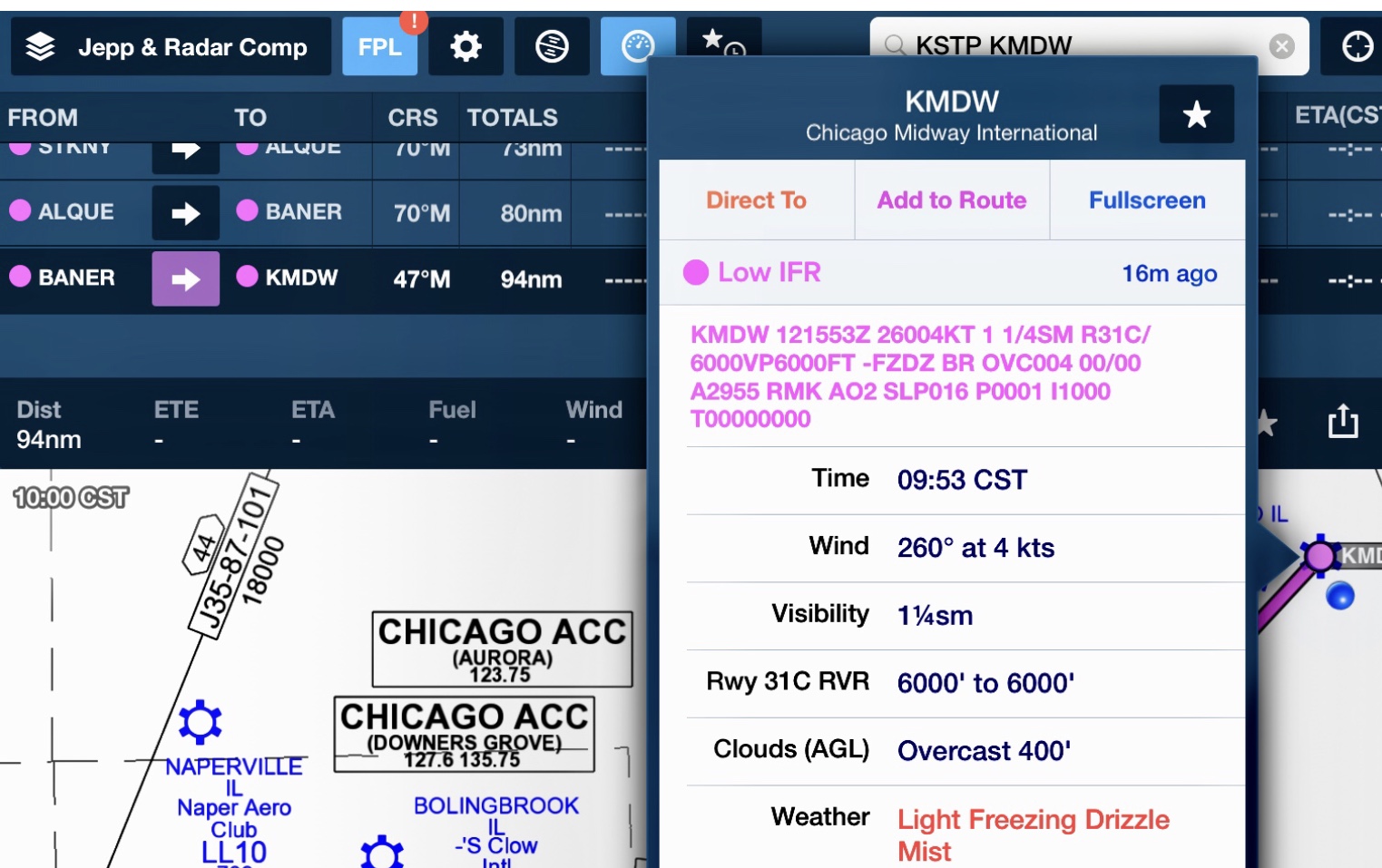

We had flown from Bermuda (predictably warm and sunny) to Teterboro (where we cleared customs and fueled) and then off to Wisconsin for meetings our clients had to attend. Our next planned leg was to Chicago Midway, and it looked impossible to me. I wasn’t even considering the possibility of flight. My elder captain was happily whistling and drinking coffee as I quietly contemplated sure death. Midway had closed all but one runway and was keeping that open with “liquid deicing.” Chemical deicing is a last resort of potassium acetate deicer applied every 20 minutes (at something like $3K a pass) This is a desperate attempt to keep the runway open for SW flights (and occasional idiots like us). And so long as they can keep some friction we are approved to land…but what about flying in this crap?

I called a friend who was an FAA Designated Engineering Representative specializing in airframe certification for icing. He cheerfully assured me that Part 25 airframes were good for 15 minutes in severe conditions. Sounds great on paper. But he also made me promise to call him back if/when we made it to Midway; not a good sign.

One fortunate fact from basic weather theory is that freezing precipitation on the surface implies warmer air aloft, and it worked out that most of the trip was in above-freezing temps. We were an hour en route, fairly ice-free, but the last 2,000ft of the descent and approach was other-worldly scary. It sounded like a carwash with gravel embedded in the mix and even with the deice at maximum (with alcohol) we could barely keep a “sight hole” open to land the jet.

One fortunate fact from basic weather theory is that freezing precipitation on the surface implies warmer air aloft, and it worked out that most of the trip was in above-freezing temps. We were an hour en route, fairly ice-free, but the last 2,000ft of the descent and approach was other-worldly scary. It sounded like a carwash with gravel embedded in the mix and even with the deice at maximum (with alcohol) we could barely keep a “sight hole” open to land the jet.

And “deiced” would be a charitable description for the runway conditions, but we landed and stopped (eventually – God bless antiskid). There was no real treatment of taxiways and ramps though; getting to Signature was tricky and deplaning passengers onto the glaze ice was similarly risky. Definitely live and learn here; certainly “can be done” but serious questions about whether it “should be done.”

I spent the next two days waiting for clients in the Marriott and watching Southwest Airlines landing 737s continuously in this amazing weather. I guess you get used to anything? Every situation has limits, the safety margins just get thinner and you certainly can see over the edge. We begged Signature to stick us in a hangar under the wing of a bigger jet (or we would have been an arctic mess). Great people, doing the best they can with Mother Nature’s worst.